Workplace Drug Testing -

Prevalence of Positive Test Results,

Most Common Substances, and

Importance of Medical Review

The following has been submitted by an MROCC-certified MRO from Sweden. A link to the full article is available below.

ABSTRACT1

Recent data indicate that the use of controlled substances is increasing in working life, which can negatively affect work environment,

performance, and safety. Many employers have an alcohol and drug policy that describes routines for preventive measures

and early detection of illicit drug use. This often includes drug tests that provide objective information about recent use,

and can be done routinely, randomly, and on suspicion. For some substances, however, a positive drug test may also result from

prescription as medicine. Controlled substances that are abused and prescribed include amphetamines (ADHD medication),

benzodiazepines and opiates. In a 2023 study of 23,900 urine and oral fluid drug test results from Swedish workplaces, 4.6%

tested positive for one or more controlled substances. Most samples were collected in connection with random testing (40%) and

new employment (36%), whereas the highest proportions of drug-positive samples were observed in cases related to accidents

or incidents, or on suspicion of drug use. The highest percentage of positive random drug tests was recorded in the construction

sector. The most common substances were cannabis (> 40% of cases), amphetamine (> 20%), and cocaine and benzodiazepines

(> 10% each). However, many samples containing opiates (71% of cases), amphetamine (63%) and benzodiazepines (44%) were

verified by a specialist trained Medical Review Officer (MRO) to be due to medical prescription, while those containing cannabis

or cocaine were almost entirely due to illicit drug use. Considering the potentially negative consequences of a positive drug test

in working life, an MRO should verify the results before they become final.

Complete article is available here.

FOOTNOTES

- Helander, A., & Sparring, F. (2025). Workplace Drug Testing - Prevalence of Positive Test Results, Most Common Substances, and Importance of Medical Review. Drug Testing and Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1002/dta.3863

MRO Responsibilities Under

10 CFR 26 (NRC) Fitness for Duty Regulation:

Testing for Other Substances of Abuse

Previous issues of the MROCC MRO Quarterly Newsletter included a detailed discussion of the MRO role in determining subversion vs. substitution and adulteration, legal medication misuse and the role of the MRO in alcohol testing under Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) regulations (10 CFR 26). Another major difference between 10 CFR 26 and the other federally regulated workplace drug testing programs is when and how other substances of abuse may be added to the required minimum panel of substances tested.

§ 26.31 Drug and alcohol testing

Essentially, there are two general categories in which to add additional substances listed on Schedules I through V (controlled substances) for testing:

- For all workers and all categories of testing when "other drugs with abuse potential are being used in the geographical locale of the facility and by the local workforce that may not detected" in the required minimum panel of drugs tested.

- For individual workers when conducting post-event, follow-up, and for-cause testing if that individual is suspected of having abused a specific drug or category of drugs.

Generally speaking, 10 CFR 26 can be thought of as a permissive regulation: there are minimum requirements that must be rigorously followed, however, if there is a reasonable rationale for more stringent standards, i.e. lower cut-off levels for screening and confirmation testing and/or for adding additional drugs to the testing panel, the NRC licensee (employer) may do so. The other Federal workplace drug testing programs (HHS, DOT) are absolute regulations: the regulation defines what must be done in nearly all instances, there are no deviations or exceptions for unusual situations.

Case Studies

CASE #1

In the initial implementation of 10 CFR 26, a nuclear licensee consulted local law enforcement regarding abuse of substances not included in the required minimum testing panel. Benzodiazepines were noted to be often abused in the local geographic area. Thus, a panel for benzodiazepines was included for all workers and all categories of testing. This continued for 2-3 years. However, nearly all confirmed positive test results were verified negative by the MRO and the licensee dropped benzodiazepine testing.

CASE #2

In May 2018, a contract carpenter was overheard stating that he was using Suboxone almost every day and "it makes him feel real good!" The witness was determined to be credible and for-cause (observed) testing with an added panel for semi-synthetic opioids performed (at that time, the HHS-Certified Laboratory performing testing did not have a forensically valid process to test for buprenorphine). All test results were negative.

However, during the MRO interview, the donor admitted the following:

- He had a long history of chronic low back pain for which he did have an old prescription in his name for hydrocodone/acetaminophen.

- He freely admitted using Suboxone that he had "borrowed" from a friend for his back pain instead of his own prescription for hydrocodone/acetaminophen.

- He had never had a prescription for Suboxone in his own name.

The MRO did a Determination of Fitness (to be detailed in a future newsletter) and, based solely on the donor's admission that he was using Suboxone from a friend and did not have a valid prescription for Suboxone in his own name, "no access" (security clearance) to work at a nuclear plant was recommended for three years.

In February 2022, this donor re-applied to work at a nuclear power plant. His past history was reviewed and an additional panel for semi-synthetic opioids as well as buprenorphine/norbuprenorphine was ordered for his Pre-Access testing. The results showed buprenorphine 19 ng/ml (confirm cutoff 5 ng/ml) and norbuprenorphine 25 (confirm cutoff 5 ng/ml).

During the MRO interview, the donor admitted to having been on monthly Sublocade 100 mg injections but was adamant that his last injection was April 1, 2021 and that he had not used any form of buprenorphine since then. He requested reanalysis of his specimen, in this case, an aliquot of the single specimen that had been collected. NOTE: Split specimens are an option, not a requirement under 10 CFR 26. Reanalysis confirmed both buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine. After thorough review of donor supplied medical records and the pharmacology of Sublocade injections, the MRO verified the results as positive, a violation of 10 CFR 26. This determination was upheld on appeal and the donor determined to be ineligible for work in the nuclear industry until completion of substance abuse evaluation, all recommended treatment and a minimum of one year sobriety.

CASE #3

Based upon credible reports, a male worker was suspected of manufacturing and using illicit anabolic steroids and "growing Spores" (possible hallucinogenic mushrooms). The MRO reviewed the situation and requested the HHS-Certified Laboratory to add testing for anabolic steroids, mescaline and psilocin. Results for the standard drugs of abuse panel, mescaline and psilocin were negative. The anabolic steroid panel tested for the presence of 22 substances. The results for all but testosterone and epitestosterone were negative. Testosterone was present at 48.2 ng/ml and epitestosterone was present at 1.6 ng/ml, giving a T/E (testosterone/epitestosterone) ration of 30.1. One of the minor metabolites of endogenous testosterone is epitestosterone and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has established that a T/E ratio > 4 is likely due to the use of exogenous testosterone. The donor T/E ratio of 30.1 is far in excess of what is expected for metabolism of endogenous testosterone alone.

Armed with this information, the MRO interviewed the donor. The donor did not have a valid prescription for testosterone and admitted injecting up to 500 mg of illicit testosterone weekly. He had attempted to stop using illegal testosterone in the past and failed. He had referred himself to EAP (Employee Assistance Program) approximately two months earlier to treat his admitted addiction to anabolic steroids. The MRO verified the results as positive, a violation of 10 CFR 26. The donor immediately resigned from his employment.

CASE #4

MRO (also certified as NRC Substance Abuse Expert or SAE) was requested to review health care records of employee returning from a prolonged medical leave of absence. As part of the Determination of Fitness process (to be detailed in a future newsletter), the MRO noted that worker had been treated by four different prescribing mental health providers, all of whom had expressed concern regarding the employee's use of Xanax (alprazolam). The employee had been repeatedly recommended to use other medications, therapy, etc and to cease all use of alprazolam. The MRO consulted with current treating psychiatrist, who agreed that alprazolam was no longer medically necessary. Therefore, the MRO recommended that return to work be allowed only as long as employee remained compliant with treatment recommendations (monitored by on-site Occupational Health nursing staff), including abstinence from alprazolam. To assure compliance with benzodiazepine abstinence, follow-up testing with an additional benzodiazepine panel was recommended.

Final Comments

These cases demonstrate the latitude given to the nuclear licensee (employer) and the MRO in protecting the safety of the workplace and the general public. 10 CFR 26 is a comprehensive Fitness for Duty regulation that includes workplace drug testing. Thus, additional tools are authorized so that one of the key performance objectives can be met:

§ 26.23 (b) Provide reasonable assurance that individuals are not under the influence of any substance, legal or illegal, or mentally or physically impaired from any cause, which in any way adversely affects their ability to safely and competently perform their duties;

The Evolving Role of

THC Testing in Clinical Practice

In States Where Marijuana is Legal

Emory University School of Medicine

The role of THC testing has undergone significant changes over the years, particularly in clinical settings where it has traditionally been used for purposes such as assessing workplace safety, monitoring patients for substance use disorders and ensuring compliance with legal or institutional policies. However, as attitudes toward cannabis have evolved and recreational marijuana has been legalized in many states, the focus of THC testing has shifted1. This transition calls for a thoughtful reconsideration of its necessity and relevance, especially in light of changing societal norms and legal landscapes.

For medical review officers (MROs), the evolving role of THC testing carries unique implications. Historically, MROs relied on THC test results to evaluate workplace safety, identify substance use issues, and enforce drug-free workplace policies. While these goals remain critical, the increasing acceptance of cannabis use challenges the traditional punitive approaches to THC testing. Instead, there is growing recognition of the need to balance responsible cannabis use with public safety and professional integrity.

The Changing Landscape of THC Testing

The legalization of recreational marijuana in numerous states has prompted a paradigm shift in how THC testing is perceived and applied. Many jurisdictions now place less emphasis on penalizing cannabis use and focus instead on fostering responsible consumption. This change requires healthcare providers, including MROs, to reevaluate the relevance of routine THC testing, particularly in non-safety-sensitive contexts.

Nonetheless, THC testing remains clinically significant in certain situations. MROs may obtain information during the testing process that can aid primary caregivers in diagnosis/treatment of patients. For instance, it can aid in diagnosing cannabis hyperemesis syndrome, a condition characterized by severe nausea and vomiting linked to chronic cannabis use. Additionally, THC testing may be necessary to evaluate impairment in patients, ensure safe administration of medical treatments, or identify potential drug interactions. In these cases, the clinical utility of THC testing is undeniable, but its application must align with contemporary attitudes toward cannabis.

Tailoring Drug Testing Panels

One emerging question for the laboratory medicine community is whether it is time to develop tailored drug testing panels that reflect the nuances of legalized marijuana. For example, should testing facilities offer separate panels that include or exclude THC to accommodate differing workplace policies, legal requirements, or clinical objectives? Such an approach could provide a more flexible framework for substance screening, allowing healthcare professionals to focus on substances most relevant to specific scenarios.

For MROs, this flexibility is particularly valuable. Tailored panels enable them to address the needs of employers who may want to exclude THC testing in non-safety-sensitive roles or prioritize other substances of abuse. Similarly, clinicians could utilize these customized panels to monitor patients without stigmatizing those who use cannabis legally.

Challenges with THC Variants

Even in states where THC remains illegal, the emergence of THC variants such as delta-8 and delta-10 has further complicated testing practices. These compounds, derived from hemp and legalized under the 2018 Farm Bill2, are chemically distinct from delta-9 THC, the primary psychoactive component of cannabis. Traditional THC testing methodologies may fail to distinguish between these variants, posing a challenge for accurate substance use assessment.

For MROs and other healthcare professionals, understanding the implications of these variants is essential. For example, delta-8 and delta-10 THC are often marketed as legal alternatives to marijuana, yet they can produce psychoactive effects that may impair judgment or motor skills. This highlights the importance of updating testing protocols to include these compounds when necessary, ensuring comprehensive and accurate evaluations.

Navigating Legal and Regulatory Complexities

Keeping pace with the evolving regulatory landscape is critical for maintaining the integrity and relevance of THC testing. Laws governing cannabis use, possession, and testing vary widely across states, creating a patchwork of legal frameworks that testing facilities and healthcare providers must navigate. MROs, in particular, play a pivotal role in interpreting these regulations and ensuring that testing practices comply with both state and federal laws.

To address these complexities, ongoing education and collaboration between healthcare professionals, MROs, testing laboratories, and policymakers are essential. Updated guidelines, robust testing methodologies, and clear communication about the scope and limitations of THC testing can help ensure its appropriate application in clinical and occupational settings.

Conclusion

The role of THC testing is undoubtedly evolving, driven by shifting societal attitudes, legal reforms, and the emergence of new THC variants. For MROs, this evolution presents both challenges and opportunities. By adopting tailored testing panels, staying informed about legal and regulatory changes, and emphasizing the relevance of THC testing, MROs can ensure that their practices remain aligned with contemporary standards.

As the conversation around cannabis continues to evolve, healthcare professionals must remain adaptable, prioritizing patient care and public safety while acknowledging the changing norms surrounding cannabis use. In doing so, THC testing can maintain its relevance as a valuable tool in clinical and occupational health.

References

Oral Fluid Testing: Don't Forget About State Laws

"I will obey every law or submit to the penalty."1

Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

Introduction2

There is much talk about the new federally approved oral fluid testing options.3 But we must remember that of the nearly fifty million drug tests conducted each year in our workplaces4, only about six million of those tests, or twelve percent, are federally regulated.5 The rest are typically governed by state or local law or applicable drug testing protocols.

Chief Joseph promised to obey every law or suffer the consequences. In his case, the consequences would be the loss of freedom and possible death. For employers and drug testing service providers, non-compliance penalties could be very costly, although perhaps not as consequential as that facing Chief Joseph.

Background: Oral Fluid Testing

Mass employee drug testing in this country can be traced back nearly forty years to President Ronald Reagan's September 15, 1986, Executive Order 12564.6 The EO required each federal agency to establish a drug-free workplace, including drug testing. Section 4 of the EO authorized the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to "promulgate scientific and technical guidelines for drug testing programs.7" It required federal agencies to conduct their drug testing programs in accordance with the guidelines once promulgated. [emphasis added]. When the final "Mandatory Guidelines" were issued on April 11, 1988, urine was the specimen chosen by HHS for testing drugs.8

Alternatives to urine testing were being explored during that same time. Detecting illicit drugs in oral fluids (saliva) was initially investigated in the early 1980s.9 In 1993, Dr. Edward J. Cone noted that "saliva has specific advantages over both blood and urine in being readily accessible for sampling and is more amenable to pharmacologic interpretation."10 In July 2004, Professor Crouch et al. reported, "Oral fluid, sometimes called 'mixed saliva,' comes from three major and several minor salivary glands. Strictly speaking, oral fluid is the mixed saliva from the glands and other constituents present in the mouth. 'Saliva' is the fluid collected from a specific salivary gland and is free from other materials."11 Professor Crouch also noted, "if saliva drug concentrations correlate with blood drug concentrations, then saliva would be an extremely valuable specimen for interpretative purposes in the criminal justice system, impaired-driving cases, and post-accident testing, and for therapeutic drug monitoring."12

Federal Rules

Consideration of alternative test methods, including oral fluid testing, began at the federal level as early as 1997.13 Fourteen years later, on July 13, 2011, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) Drug Test Advisory Board (DTAB) voted to recommend that SAMHSA include oral fluid as an alternative specimen in the Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs.14 On January 27, 2012, the Secretary of Transportation, through the Office of Drug and Alcohol Policy and Compliance (ODAPC), announced that the Department would work with DTAB, SAMHSA, and the Office of National Drug Control Policy and others "to bring these approved recommendations to realization" throughout the transportation industry.15

Over the subsequent fourteen years since DTAB recommended oral fluid testing, the regulatory process has been working toward finally implementing that recommendation. On October 25, 2019, SAMHSA issued amendments to the Mandatory Guidelines that presented standards and technical requirements for oral fluid collection devices, initial oral fluid drug test analytes and methods, confirmatory oral fluid drug test analytes and methods, processes for review by a Medical Review Officer (MRO), and requirements for federal agency actions.16 The Department of Transportation (DOT) version of those rules was finalized on May 2, 2023.17

DOT defines specimen as: "Fluid, breath, or other material collected from an employee at the collection site for the purpose of a drug or alcohol test."

State Laws

Approximately 88% of all workplace drug tests are non-regulated. But that doesn't mean these tests are not subject to limitations. A patchwork of state and local laws impacts employer drug testing programs. To decipher the rules in these states, employers must first determine the 'nature' of the state. There are four categories of states:

- Mandatory states, meaning any employer wishing to conduct employee drug testing, must follow state or local rules.

- Voluntary states where employers choose to comply with state rules to obtain some benefit. (Workers' Compensation Insurance Premium Discounts, claim defenses, etc.)

- Required states where employers in specific industries must conduct drug testing and;

- Open states that have no employment drug testing rules.

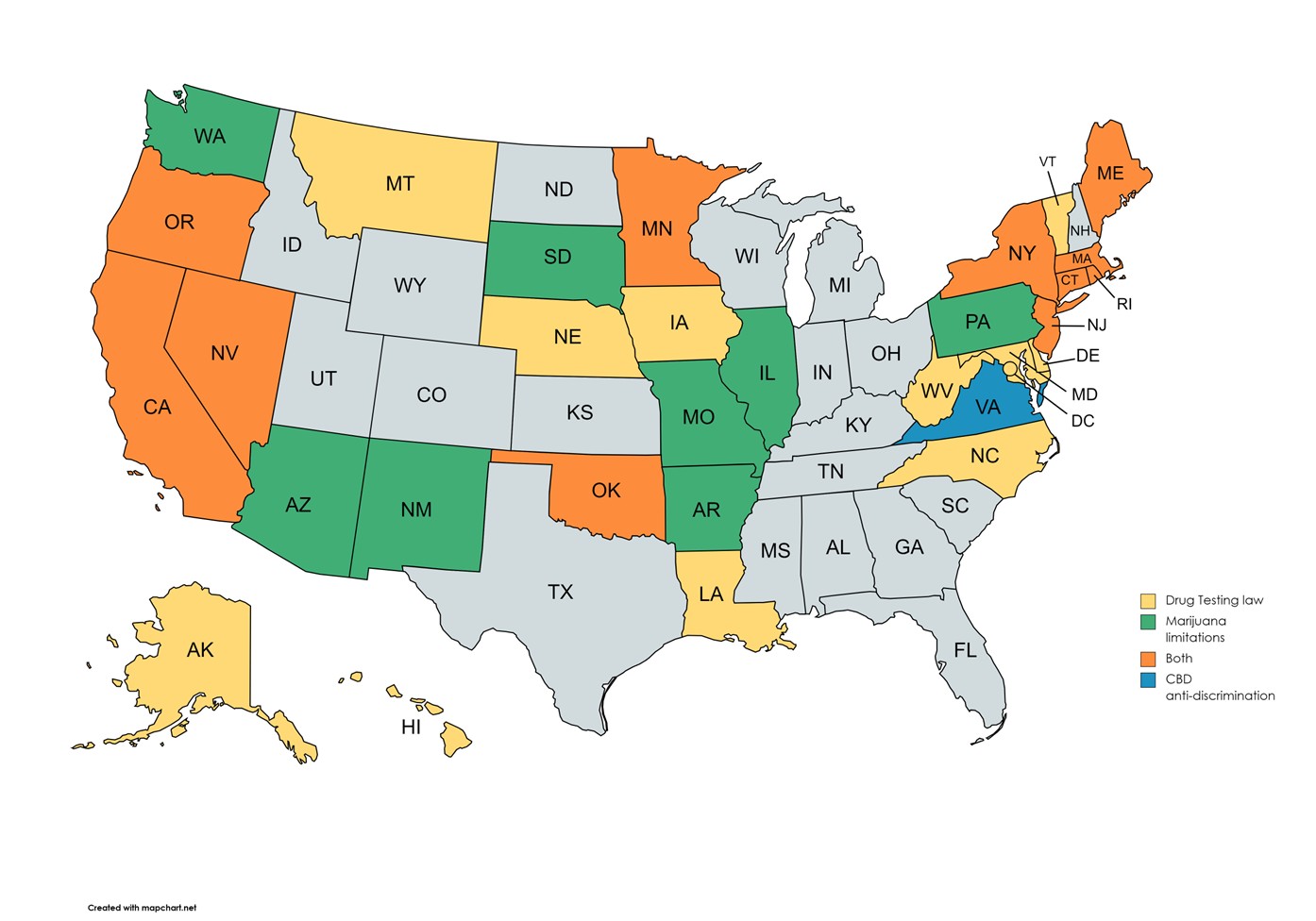

As it stands today, there are 31 states with mandatory drug testing rules. (See map below) These states are considered mandatory either because of drug testing limitations imposed by statute, regulation, or court decisions or due to the growing number of cannabis legalization laws.

Employers in these 31 states must abide by the state's rules. These rules vary dramatically by state and impact the who, what, when, where, why, and how testing is conducted and what disciplines employers can impose.

Voluntary states include:

- 12 states with Drug-Free Workplace workers' compensation premium discount programs (typically 5% discount),

- 21 states with a rebuttable presumption of intoxication defenses to a workers' compensation claim,

- Nearly all states offer an unemployment claim defense, and;

- States with immunity defenses (relief from being sued) for employers who choose to follow the state rules.

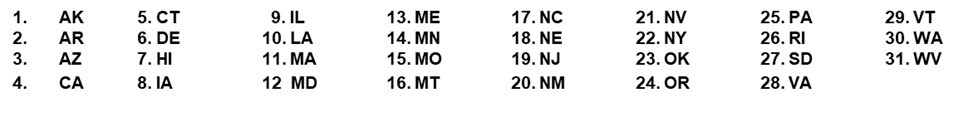

Some states have straightforward rules; others are incredibly detailed and complex. By just one example and one of particular interest, here are the 21 states requiring employment testing programs to utilize a Medical Review Officer (MRO). (See the map below).

States that Require an MRO

State Laws and Oral Fluid Testing

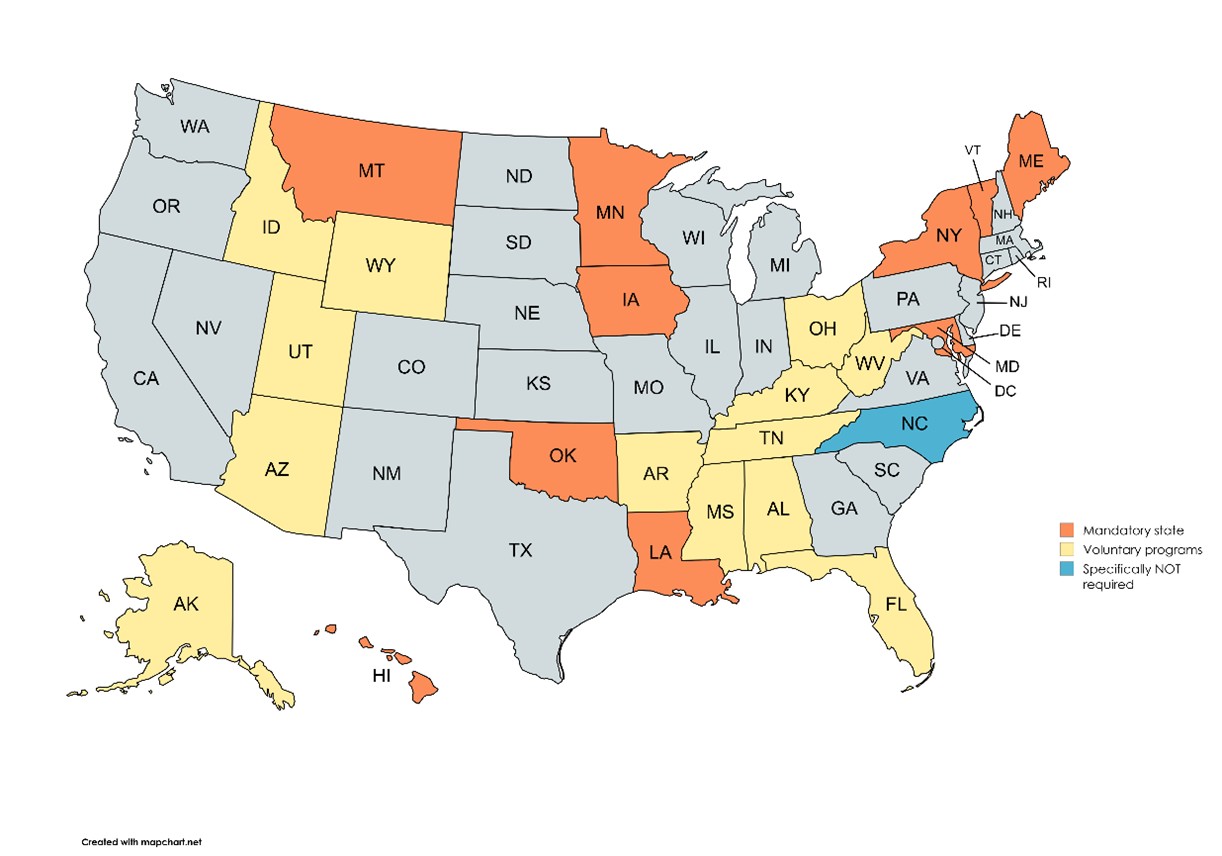

While the federal government has authorized oral fluid testing of regulated workers (not available today - still pending implementation), the option to utilize oral fluid testing has been available for screening non-regulated workers for decades. Before conducting workplace drug testing using oral fluid, employers must review the laws of the states or municipalities where they operate to see if oral fluid testing is permitted.

Thirty-one states and Boulder, CO define the terms "specimen" or "sample." (See map below and for details, see Attachment "A"). Read the statute or ordinance carefully. There are ten variations to the definition of specimen or sample.

To see if the state's definition impacts your program, employers must first ask whether the rule is mandatory, voluntary, or required. If it's voluntary, employers can choose whether to participate in the program to raise the defense or otherwise leverage the financial benefit. For mandatory states, employers have no choice.

Those variations range from the straightforward "material derived from the human body"18 to the more complex "Sample means urine, blood, breath, saliva, hair or other substances from the person being tested."

There are fourteen "state programs" that require following federal DOT rules, which define "specimen" as "Fluid, breath, or other material collected from an employee at the collection site for the purpose of a drug or alcohol test"19 and nine states that require following HHS guidelines, which defines "specimen" as, "Fluid or material collected from a donor at the collection site for the purpose of a drug test."20 The SAMHSA Mandatory Guidelines also specify that "Oral Fluid Specimen: An oral fluid specimen is collected from the donor's oral cavity and is a combination of physiological fluids produced primarily by the salivary glands."

A complete analysis of the differences between state/local law and federal rules is beyond the scope of this article. But to highlight the complexities involved with just a few examples, consider the following:

- If you expect to defeat a workers' compensation claim based on a positive drug test in Alabama,21 Florida,22 or Texas,23 employers cannot use oral fluid as a means of testing.

- Cutoff levels may differ or not be specified under state law. For example, the SAMHSA and DOT initial cutoff levels for marijuana using oral fluid are 4ng/mL. The Oklahoma Administrative Code § 310:638-1-7.2 states in part, "The manufacturer of the saliva test system shall establish confirmation cutoff levels to be used when confirming saliva specimens that screen positive."

- Some states may limit the use of Point-of-Collection Testing (POCT) devices versus lab-based oral fluid testing.

SAMHSA and DOT rules are detailed, while state laws typically do not have sample collection procedures. For example, federal regulations require the collector to be trained, require a specific volume of "neat" oral fluid to be collected, each collection must be a split sample collection of at least 1mL in each "tube," and much more.

Conclusion

Oral fluid testing has been successfully utilized in non-regulated workplace programs for many decades. As employers and service providers across our nation patiently await the final approvals and the inevitable implementation challenges for DOT oral fluid testing, those offering or utilizing oral fluid testing for non-regulated programs should understand that state and local rules may limit their options.

If you have any questions, JUST ASK!

www.AskBillJudge.com

Bill Judge

866-775-3724

FOOTNOTES

- Excerpted from the speech Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce delivered at Lincoln Hall in Washington, D.C. on January 14th, 1879. Published in North American Review, Vol. 128, Issue 269, pp. 412-434. Courtesy of Cornell University's Making of America and found at https://s3.greatminds.org/link_files/files/000/000/740/original/05.01.L29a_Handout.pdf?1522687292. It has been explained that this quote . . . "highlights the individual's recognition of their civic duty and the implicit understanding that failure to comply with the law will inevitably result in appropriate punishment." https://www.socratic-method.com/quote-meanings/chief-joseph-i-will-obey-every-law-or-submit-to-the-penalty.

- At the outset I want to beg your forgiveness for my feeble attempts to explain scientific and medical issues in this article.

- On February 28, 2022, the Federal DOT announced a proposed rule making in the Federal Register (87 FR 11156) to provide regulated employers the option to conduct oral fluid testing. DOT's intent was also to "harmonize" its rules with those announced on

- https://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/cover_story/2015/12/workplace_drug_testing_is_widespread_but_ineffective.html, quoting Dr. Barry Sample who at the time was the Director of Science and Technology for the Employer Solutions business unit of Quest Diagnostics.

- See 87 Fed. Reg. 39039, (06/30/2022). Additionally there are an estimated 275,000 urine samples conducted for federal employees. See, 88 Fed. Reg. No. 196 at p 70768. According to the latest statistics there are more than 5 million commercial drivers registered with the FMCSA Clearinghouse. (https://clearinghouse.fmcsa.dot.gov/content/resources/Clearinghouse_MonthlyReport_July2024.pdf).

- 51 FR 32889, 3 CFR 1986.

- Secretary of HSS assigned responisiblity for these guidelines to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). In 1992, SAMHSA was established by congress as part of the reorganization of HHS. SAMHSA was then assigned the responsibility of promulgating scientific and technical guidelines for drug testing programs.

- Mandatory Guidelines, sec. 2.1(c), 53 FR 11960. The term "specimen" was not defined.

- Peel, H. W., Perrigo B. J., and Mikhael N. Z. (1984), Detection of drugs in saliva of impaired drivers. J. Forensic Sci. 29, 185-189; Forensic Science: On-Site Drug Testing, Edited by: A. J. Jenkins and B. A. Goldberger ©Humana Press, Inc., ch. 8, p. 95, Totowa, NJ.

- Cone, Saliva Testing for Drugs of Abuse, 1993, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14984370_Saliva_Testing_for_Drugs_of_Abuse.

- Crouch et al, Evaluation of Saliva/Oral Fluid as an Alternate Drug Testing Specimen at p. 1, NIJ Report 605-03, https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/203569.pdf

- Crouch et al, Evaluation of Saliva/Oral Fluid as an Alternate Drug Testing Specimen at p. 15, NIJ Report 605-03, https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/203569.pdf .

- See 80 FR 28056 (May 15, 2015).

- https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/USDOT/2012/01/27/file_attachments/89677/DTAB%2Brecommendation%2Bmemo%2Bsigned.pdf.

- https://content.govdelivery.com/bulletins/gd/USDOT-284bcb.

- 84 FR 57557, October 25, 2019.

- 88 FR 27596, May 2, 2023.

- Oregon (ORS 438.010(19)), Vermont (Vt. Stat. tit. 21 §511), and West Virginia (Art. 3E, The West Virginia Safer Workplace Act.)

- 88 FR 27637.

- 84 FR 57580.

- Ala. Admin Code Reg. §480-5-6-.03(1)(a).

- Chapter 59A-24.004 Florida Admin Code.

- Texas Code Sec. 401.013(c).

- See Federal Mandatory Guidelines at Section 2.4; DOT at part 40.74. Note DOT refers to the containers as "bottles" not tubes.

FMCSA Medical Review Board

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), an agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), is responsible for regulating the commercial trucking and bus industries to enhance road safety. A key part of this mission is establishing and enforcing medical requirements for commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers. In 2006, the Medical Review Board (MRB) was established to assist FMCSA in this effort by providing expert medical advice on medical conditions that could affect drivers' ability to safely operate a CMV. FMCSA recognizes that the current physical qualification standards published in 49 CFR 391.41(b)(1-13) do not fully address new medical treatments. One role of the MRB is to review the FMCSA physical qualification standards for medical certification of CMV drivers and provide science-based recommendations to the Secretary of Transportation and the FMCSA Administrator on modification and/or addition of medical standards and guidelines based on up-to-date research and standard medical practice.

The MRB consists of a panel of physicians, appointed by the Secretary of Transportation, that have specialties relevant to FMCSA's bus and truck driver fitness requirements. The MRB plays a crucial role in improving highway safety by reducing the risk of crashes caused by medical impairments. The MRB advises FMCSA through science-based guidance on physical qualification standards for CMV drivers, medical examiner education, medical standards and guidelines. The MRB also evaluates and provides recommendations to the FMCSA about regulations that may need to be changed or updated.

The primary function of the MRB is to evaluate the FMCSA physical qualification standards and the potential impact of medical conditions on drivers' ability to perform essential job functions. The MRB frequently updates its recommendations based on current medical research and advances in healthcare. The MRB studies various medical conditions that may impact driving ability and has established medical guidelines that balance driver safety with the industry's workforce needs. Some recent topics addressed by the MRB include:

- Cardiovascular Disease — Evaluating risks associated with heart conditions, hypertension, and other cardiovascular issues.

- Diabetes — Reviewing the safety of insulin-treated drivers and updating FMCSA's diabetes exemption program.

- Neurological Disorders — Assessing conditions like epilepsy, seizures, and stroke recovery in relation to safe driving.

- Mental Health — Advising on psychiatric conditions, medication use, and their effects on driving safety.

- Sleep Apnea — Recommending screening and treatment guidelines for obstructive sleep apnea, a condition linked to driver fatigue.

- Vision — Reviewing the safety of visual impairment and updating FMCSA's vision exemption program.

The MRB provides science-based recommendations to FMCSA for development and implementation of physical qualification standards based on up-to-date research and current medical standards of practice. The MRB does not create regulations or make program decisions but provides science-based recommendations to FMCSA on revising medical regulations. In addition to MRB recommendation, FMCSA considers industry concerns, legal factors, and public input before final rulemaking. The MRB makes recommendations to FMCSA in areas such as:

- Medical Qualification Standards — Reviewing and updating the medical criteria CMV drivers must meet.

- Guidance for Medical Examiners — Advising certified medical examiners on best practices for assessing driver fitness.

- Policy Development — Suggesting changes to FMCSA policies based on medical advancements and safety data.

- Public and Stakeholder Engagement — Working with industry groups, healthcare providers, and drivers to improve medical certification standards.

The MRB's work is not without challenges. Some of the key issues include:

- Balancing Safety with Industry Needs: While the MRB prioritizes road safety, stricter medical requirements can limit the number of qualified drivers, exacerbating labor shortages in the trucking industry.

- Scientific Uncertainty: Some medical conditions do not have clear-cut guidelines for assessing risk, making it difficult to develop universally accepted standards.

- Regulatory Delays: Even when the MRB recommends changes, implementing new medical rules can take years due to the complex regulatory process.

- Legal and Political Considerations: Driver advocacy groups, employer associations, and medical professionals often have differing opinions on proposed changes, leading to ongoing debates over medical certification policies.

Despite these challenges, the MRB remains a key contributor to FMCSA policy by ensuring that medical standards evolve alongside scientific advancements.

FMCSA's MRB plays a vital role in maintaining road safety by evaluating medical conditions that could impair CMV drivers. Through expert recommendations, the MRB helps shape medical certification standards, ensuring that only medically qualified individuals operate commercial vehicles. While challenges exist in balancing safety with industry demands, the MRB's work is essential in reducing crashes and improving the overall health of the commercial driving workforce. As medical science advances, the MRB will continue to play a crucial role in adapting FMCSA policies to ensure a safe and efficient transportation system.

HHS Revised Authorized Testing Panels

On January 16, 2025, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released its Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs-Authorized Testing Panels detailing updated Authorized Testing Panels for urine and oral fluid drug testing. These revisions will take effect on July 7, 2025, and apply only to federal agency workplace drug testing programs, not to federally regulated drug testing programs under the Department of Transportation (DOT), including USCG, or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

Details of the update:

- Fentanyl has been added to the testing panel. Urine: Fentanyl screening 1 ng/mL; Fentanyl/norfentanyl confirmation 1 ng/mL. Oral Fluid: Fentanyl screening 4 ng/mL; Fentanyl confirmation 1 ng/mL.

- Criteria for grouped analytes have been revised for associated alternate technology initial drug tests.

- Abbreviations for THC and its metabolites have been updated. The new abbreviations are Δ9THC in place of THC and Δ9THCC in place of THCA.

- The current panels will remain in effect through July 6, 2025.

- HHS has not approved biomarker testing for federal workplace drug testing.

Important notes:

- This update applies exclusively to federal agencies governed by HHS UrMG and OFMG.

- DOT and NRC testing programs remain unaffected at this time.

- DOT and NRC must issue their own rules to conform to these revisions before they apply to their programs.

- DOT has not yet adopted the 10/12/23 HHS UrMG revision to a 4000 ng/mL morphine confirmatory cutoff.

The full notice is available in the Federal Register by clicking here.

ODAPC - DOT

- Office of Drug & Alcohol Policy & Compliance (ODAPC)

- DOT 49 CFR Part 40 Procedures for Transportation Workplace Drug and Alcohol Testing Programs

- Subscribe to the ODAPC Updates and News

- 2024 DOT Random Testing Rates

SAMHSA - HHS

- Medical Review Officer Guidance Manual for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs

- Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs using Urine (UrMG)

- Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs using Oral Fluid (OFMG)

NRC

CUSTODY AND CONTROL FORMS (CCFs)

- 2020 Federal CCF for Urine and Oral Fluid Specimens

- 2020 Guidance for Using the Federal CCF for Urine Specimens

Medical Review Officer

Certification Council (MROCC)

3231 S Halsted St, Ste Front #167

Chicago, IL 60608

Tel: 847.631.0599

Email: mrocc@mrocc.org

Co-editor: James Ferguson, DO

Co-editor: Donna Smith, PhD

Managing Editor: Kristine Pasciak

©2024 Medical Review Officer Certification Council

ISSN: 2833-0870

MRO Quarterly is an educational publication intended to provide information and opinion to health professionals. The statements and opinions contained in this document are solely those of the individual authors/contributors and not MROCC. MROCC and its editorial staff disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any ideas or products referred to in this newsletter.

To unsubscribe from MROCC emails, please send an email to mrocc@mrocc.org with the subject unsubscribe.